Reflections on the suffering, crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus

By Dr. William Robert Da Silva

Edited by Dr Radhika Pandit, UK

Bellevision Media Network

30 Mar 2013:

[Recently Professor Dr. William Robert Da Silva, our most erudite teacher in Europe and India and trainer and guide in multidisciplinary sciences was in UAE, flying for the first time after ten years and surviving life threatening illness. As he relaxed he sat at his online survey of biblical research, he collected material for a module on the Hebrew and Greek Bible, both Jewish and Christian, on the four Gospel accounts of the passion, death by crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. It is part of a Postgraduate Diploma in religious studies at his newly founded The Mangalore Graduate School, Mangalore. I am sharing a brief account on the eve of the Easter Triduum. He sent it to me in UK to edit and publish. I am part of his editorial and publishing team. It might interest the ‘Belle Vision’ readers. The present text is material which appeared Biblical Archaeological Review or BAR arranged in an narrative mode. See Biblical Archaeologist]

THE EASTER FEAST

Easter in English, Ostern in German refer to the spring festival of the Anglo-Germanic people symbolized by the hare, [Remember: ‘rrunning with the hares and hunting with the hounds’?] ‘laying eggs.’ So, the Jewish festival of Pesach, Latin Pasca, French Paque, is celebrated by the Nordic people with ‘bunnies and eggs.’ These eggs are a boiled and painted lot today all over Europe, today globally for Easter market.

Pesach or Pasca or Passover was a Jewish ritual memorial of the exodus of Hebrew people from Egypt and celebrated with a meal called ‘seder.’ [Look up the names such as Pascal, Pascalina, Pasco, Paskina etc. in memory of Latin Pasca among Konkani Christians]

THE JEWISH SEDER

THE LAST SUPPER: A MEAL OR A SEDER?

What Jesus did at the Last Supper has not been understood for about 2,000 years. The reason for the misunderstanding is that Jesus, a Jewish teacher who was concerned with the sacrificial worship of Israel, has been treated as if he were the deity in a Hellenistic cult.

A generation after Jesus’ death, when the Gospels were written, the Romans had destroyed the Jerusalem Temple (in 70 C.E.); the most influential centres of Christianity were cities of the Mediterranean world such as Alexandria, Antioch, Corinth, Damascus, Ephesus and Rome. Although large numbers of Jews were also followers of Jesus, non-Jews came to predominate in the early Church. They controlled how the Gospels were written after 70 C.E. and how the texts were interpreted.

THE LAST SUPPER OR SEDER?

THE EUCHARIST—EXPLOORING ITS ORIGINS

Many people assume that Jesus’ Last Supper was a Seder, a ritual meal held in celebration of the Jewish holiday of Passover. And, according to the Gospel of Mark 14:12, Jesus prepared for the Last Supper on the “first day of Unleavened Bread, when they sacrificed the Passover lamb.” If Jesus and his disciples gathered together to eat soon after the Passover lamb was sacrificed, what else could they possibly have eaten if not the Passover meal? And if they ate the Passover sacrifice, they must have held a Seder.

Three out of four of the canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) agree that the Last Supper was held only after the Jewish holiday had begun. Moreover, one of the best known and painstakingly detailed studies of the Last Supper—Joachim Jeremias’s book The Eucharistic Words of Jesus—lists no fewer than 14 distinct parallels between the Last Supper tradition and the Passover Seder.

The Eucharist or the Seder?

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED AT GETHSEMANE?

The Gethsemane has stimulated the creative imagination of great painters. The scene took place in the light of a full moon with the shadows in a garden at the foot of the Mount of Olives. A lonely figure prays in anguish. His companions ignore his agony. Deep in careless sleep, the swords of the approaching soldiers they do not hear. The tension is palpably everywhere.

Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane is the most soul-wrenching: “My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me. Yet, not as I will but as you (will)” (Matthew 26:39).

At the Transfiguration Jesus is (mystically) transformed in the presence of Moses and Elijah—Jesus at his highest, here we see him at his lowest. The radiant Lord who stood erect on a mountain peak now struggles for light in the desolation of night. The disciples who were so attentive at the Transfiguration and begged to prolong the golden moment, do not want to hear or see what is happening to Jesus here.

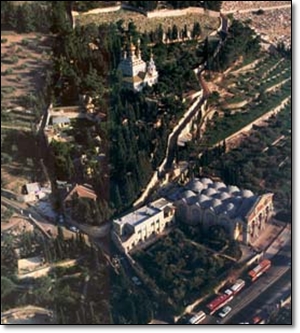

THE GARDEN OF GETHSEMANE: NOT THE PLACE OF JESUS’ ARREST

THE CAVE OF GETHSEMANE

When visitors to Jerusalem are shown a large cave called Gethsemane on the lower slopes of the Mount of Olives, they usually give a perfunctory look and hurry on to the famous Garden of Gethsemane, the small garden of olive trees adjacent to the Church of All Nations. Here pilgrims can sit and reflect on the momentous events of Jesus’ arrest in what seems a more appropriate, if less authentic, environment.

Most of these pilgrims are never told that the New Testament does not mention a Garden of Gethsemane. The Cave of Gethsemane, on the other hand, is very probably a genuine Biblical site—the location of Jesus’ arrest—unlike so many of the traditional holy sites of Christianity that have little or no claim to authenticity.

THE GARDEN OF GETHSEMANE

THE GEOGRAPHY OF FAITH

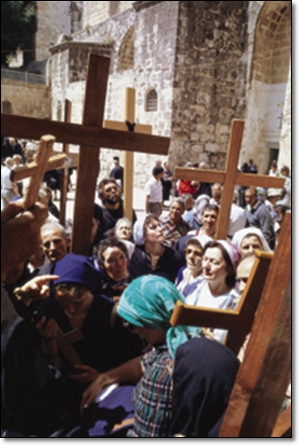

The Latin words Via Dolorosa mean the “Sorrowful Way.” They were first used by the Franciscan Boniface of Ragusa in the second half of the 16th century as the name of the devotional walk through the streets of Jerusalem that retraced the route followed by Jesus as he carried his cross to Golgotha. It is also known as the Via Crucis, the “Way of the Cross.” Today it is divided into 14 segments by a series of stops, called stations, where pilgrims pray (see map of Via Dolorosa route). The fourteen stations are one, Christ is condemned to death by Pontius Pilate (Mark 15:6–20), and thirteen other stations, until burial.

TRACING THE VIA DOLOROSA

JESUS’ TRIUMPHAL MARCH TO CRUCIFIXION

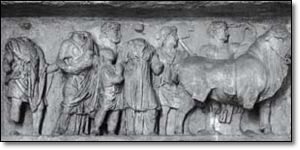

THE SACRED WAY AS ROMAN PROCESSION

Scholars have long recognized that the Evangelists do not simply report the events of Jesus’ life. They select, arrange and modify material at their disposal to stress important themes—like the connection between Jesus and the Old Testament, the inclusion of gentiles in the kingdom and the nature of discipleship.

Mark’s gospel was probably written for gentile Christians living in Rome. Could this audience have understood the various allusions to the Hebrew Bible worked into Mark’s narrative? On the other hand, Mark’s contemporaries might well have grasped a pattern of meaning that has gone unrecognized by modern Bible commentators: In Mark’s gospel, the crucifixion procession is a kind of Roman triumphal march, with Jerusalem’s Via Dolorosa replacing the Sacra Via of Rome. In this way, Mark presents Jesus’ defeat and death, the moment of his greatest suffering and humiliation, as both literally and figuratively a triumph.

CRUCIFIXION—THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

From ancient literary sources we know that tens of thousands of people were crucified in the Roman Empire. In Palestine alone the figure ran into the thousands. Yet until 1968 not a single victim of this horrifying method of execution had been uncovered archaeologically.

In that year was excavated the only victim of crucifixion ever discovered. He was a Jew, of a good family, who may have been convicted of a political crime. He lived in Jerusalem shortly after the turn of the era and sometime before the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

NEW ANALYSIS OF THE CRUCIFIED MAN

In 1985 an article appeared in an archaeological journal about the only remains of a crucified man to be recovered from antiquity (Crucifixion—The Archaeological Evidence, BAR 11:01). Vassilios Tzaferis, the author of the article and the excavator of the crucified man, based much of his analysis of the victim’s position on the cross and other aspects of the method of crucifixion on the work of a medical team from Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School headed by Nico Haas, who had analyzed the crucified man’s bones. In a recent article in the Israel Exploration Journal, however, Joseph Zias, an anthropologist with the Israel Department of Antiquities, and Eliezer Sekeles of Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem question many of Haas’s conclusions concerning the bones of the crucified man. The questions Zias and Sekeles raise affect many of the conclusions about the man’s position during crucifixion.

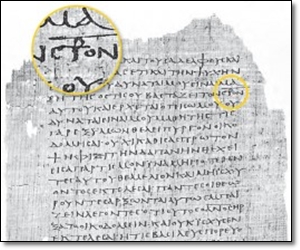

The Staurogram

The earliest images of Jesus on the cross

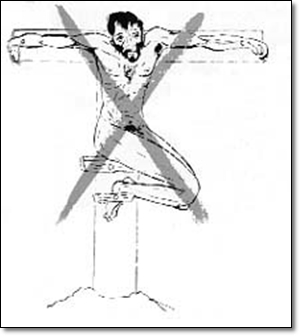

The staurogram combines the Greek letters tau-rho to stand in for parts of the Greek words for “cross” (stauros) and “crucify” (stauroō) in Bodmer papyrus P75. Staurograms serve as the earliest images of Jesus on the cross, predating other Christian crucifixion imagery by 200 years.

How and when did Christians start to depict images of Jesus on the cross? Some believe the early church avoided images of Jesus on the cross until the fourth or fifth century. In “The Staurogram: Earliest Depiction of Jesus’ Crucifixion” the March/April 2013 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review, Larry Hurtado highlights an early Christian crucifixion symbol that sets the date back by 150–200 years.

Larry Hurtado describes how a symbol known as a staurogram is created out of the Greek letters tau-rho: “In Greek, the language of the early church, the capital tau, or T, looks pretty much like our T. The capital rho, or R, however, is written like our P. If you superimpose the two letters, it looks something like this: ![]() . The earliest Christian uses of this tau-rho combination make up what is known as a staurogram. In Greek the verb to ‘crucify’ is stauroō; a ‘cross’ is a stauros … [these letters produce] a pictographic representation of a crucified figure hanging on a cross—used in the Greek words for ‘crucify’ and ‘cross.’”

. The earliest Christian uses of this tau-rho combination make up what is known as a staurogram. In Greek the verb to ‘crucify’ is stauroō; a ‘cross’ is a stauros … [these letters produce] a pictographic representation of a crucified figure hanging on a cross—used in the Greek words for ‘crucify’ and ‘cross.’”

The tau-rho staurogram is one of several christograms, or monogram-like devices used by ancient Christians, to refer to Jesus. However, Larry Hurtado points out that the staurogram only refers to the crucifixion, unlike others, which mention Jesus’ other characteristics. Also, the staurogram is visual—the tau-rho combinations create images of Jesus on the cross, making the staurogram the earliest Christian images of Jesus on the cross.

The tau-rho staurogram, like other christograms, was originally a pre-Christian symbol. A Herodian coin featuring the Staurogram predates the crucifixion. Soon after, Christian adoption of staurogram symbols serve as the first visual images of Jesus on the cross.

Larry Hurtado writes: “In time christograms came to be used not only in texts but as free-standing symbols of Christ or Christian faith, for example on liturgical vestments and church utensils. This was probably also true of the staurogram, tau-rho; where it would represent simply an independent symbol of Christ or Christian faith. But the earliest use of the tau-rho was as a visual reference to Jesus’ crucifixion. As such, it is the earliest surviving depiction of Jesus’ crucifixion.”

Roman Crucifixion Methods and Jesus’ Crucifixion 03/27/2013

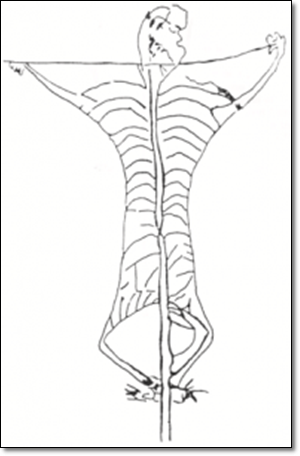

This second-century graffito of a Roman crucifixion from Puteoli, Italy, is one of a few ancient crucifixion images that offer a first-hand glimpse of Roman crucifixion methods and what Jesus’ crucifixion may have looked like to a bystander.

Crucifixion images abound today—from sculptures and icons in churches to the masterful paintings hanging in museums. But how many of these actually give us a realistic idea of what Jesus’ crucifixion looked like? Do these artistic crucifixion images accurately reflect ancient Roman crucifixion methods?

In the March/April 2013 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review, Biblical scholar Ben Witherington addresses these questions by looking at some of the earliest archaeological evidence of crucifixion and imagery roughly contemporary with Jesus’ crucifixion. Witherington discusses three crucifixion images—two wall graffiti and a magical amulet—from the first centuries of the Christian era.

The two graffiti were both discovered in Italy—one, the so called Alexamenos graffito, on the Palatine Hill in Rome and the other (pictured right) in Puteoli during an excavation. Both show a crucified figure on a cross and date to sometime between the late first and mid-third centuries A.D. Likewise, a striking red gemstone bears a crucified figure surrounded by a magical inscription.

All three of these ancient crucifixion images shed light on the reality of Roman crucifixion in practice and share a few features in common: The crosses are in the shape of a capital tau, or Greek letter T; the Puteoli graffito and the gemstone seem to depict figures who have been whipped or flayed; all three figures appear to be nude, perhaps explaining why at least two of them are shown from behind; and in each case, the feet seem to be apart and possibly nailed separately (unlike the overlapping feet of Jesus in popular portrayals). That last feature is supported by the well-known ankle bone of a crucified man discovered in Jerusalem, which still had an iron nail embedded in its side.

Assuming that Roman crucifixion methods were similar throughout the empire, these crucifixion images give us a more authentic depiction of how Jesus’ crucifixion was carried out.

WHAT DID JESUS’ TOMB LOOK LIKE?

THE TOMB WITH ROUND STONE

According to the Gospels, Jesus died and was removed from the cross on a Friday afternoon, the eve of the Jewish Sabbath. A wealthy follower named Joseph of Arimathea requested Pontius Pilate’s permission to remove Jesus’ body from the cross and bury him before sundown, in accordance with Jewish law. Because there was no time to prepare a grave before the Sabbath, Joseph placed Jesus’ body in his own family’s tomb.

The reliability of the Gospel accounts—which were written a generation or two after Jesus’ death—is debated by scholars. Most discussions have focused on literary and historical considerations, such as the composition dates of the Gospels and internal contradictions and differences between them. Here, I will consider the account of Jesus’ burial in light of the archaeological evidence. I believe that the Gospel accounts accurately reflect the manner in which the Jews of ancient Jerusalem buried their dead in the first century.

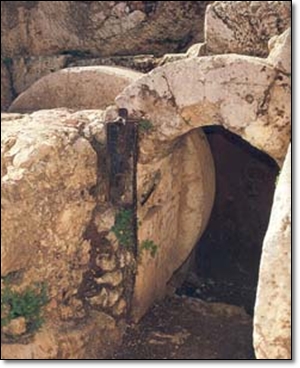

DID A ROLLING STONE CLOSE JESUS’ TOMB?

THE TOMB WITH ROLLING STONE

We should have a very good idea what Jesus’ tomb looked like, with the references in the Gospels and our knowledge of contemporaneous tombs found in and around Jerusalem. Yet until now, most of the reconstructions of this most famous of tombs have, I believe, been wrong.

The most surprising of my findings is that the blocking stone in front of the tomb was square, not round. So it could not, as many New Testament translations have it, be “rolled away”; it could only be pulled back or away.

As we shall see, the archaeological evidence for my new reconstruction is clear enough. The gospel texts, however, will need some explaining.

Let’s begin at the entrance to the tomb. It is true that the massive blocking stones (in Hebrew, golalim; singular, golel orgolal) used to protect the entrances to tombs in Jesus’ day came in two shapes: round and square. But more than 98 percent of the Jewish tombs from this period, called the Second Temple period (c. first century B.C.E. to 70 C.E.), were closed with square blocking stones. Of the more than 900 burial caves from the Second Temple period found in and around Jerusalem, only four are known to have used round (disk-shaped) blocking stones.

THE GARDEN TOMB: WAS JESUS BURIED HERE?

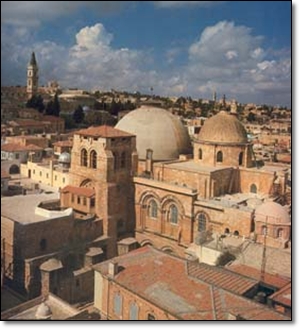

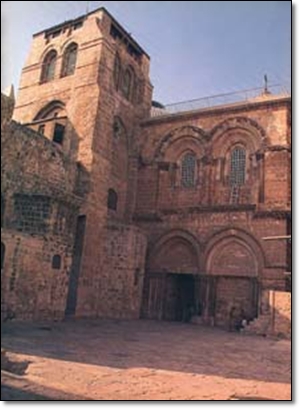

First-time visitors to Jerusalem are often surprised to learn that two very different sites vie for recognition as the burial place of Jesus. One is, as its name implies, the Holy Sepulchre Church; it is located in a crowded area of the Christian Quarter inside the walled Old City. The other, known as the Garden Tomb, is a burial cave located outside the Old City walls, in a peaceful garden just north of the Damascus Gate.

The case for the Holy Sepulchre Church as the burial place of Jesus has already been made.

But what of the Garden Tomb? What is its claim to authenticity?

DOES THE HOLY SEPULCHRE CHURCH MARK THE BURIAL OF JESUS?

THE HOLY SEPULCHE CHURCH

Since 1960, the Armenian, the Greek and the Latin religious communities that are responsible for the care of the Holy Sepulchre Church in Jerusalem have been engaged in a joint restoration project of one of the most fascinating and complex buildings in the world.

In connection with the restoration, they have undertaken extensive archaeological work in an effort to establish the history of the building and of the site on which it rests. Thirteen trenches were excavated primarily to check the stability of Crusader structures, but these trenches also constituted archaeological excavations. Stripping plaster from the walls revealed structures from earlier periods. A new, modern drainage system was put in place, but the work itself was also used for archaeological research. Elsewhere, soundings were made for purely archaeological purposes.

THE HOLY SEPULCHER CHURCH

THE MANY ENDINGS OF THE GOSPEL OF MARK

Francis Ford Coppola filmed two endings for Apocalypse Now, and John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman offers a choice of endings. But nothing quite matches the last chapter of the Gospel of Mark for variety. At least nine versions of the ending of Mark can be found among the 1,700 surviving ancient Greek manuscripts and early translations of the gospel.

The differences are not insubstantial. The shortest form ends with the three women at the tomb. The stone is rolled back, the body is gone. An angelic figure informs the women that Jesus has been raised from the dead, but Jesus himself is never seen again. The women, the final verse (Mark 16:8) of this short form records, are so frightened they run away and don’t tell anyone what they have seen—or failed to see.

EMMAUS-NICOPOLIS WHERE CHRIST APPEARED

BREAKING BREAD AT EMMAUS

At dawn the tomb of Jesus was found empty. Later that very day two of the disciples, Cleopas and another unnamed, were walking on the road to Emmaus when Jesus appeared to them, but they did not recognize him. As they drew near Emmaus, Jesus went to go on, but they pressed him to stay with them, saying, “It is toward evening and the day is now far spent.” At dinner, Jesus blessed the bread and gave it to them and “their eyes were opened and they recognized him.” All this occurred at a place called Emmaus. That same hour they returned to Jerusalem, where they told the others what had happened. And he appeared to them again! Jesus ate some fish that they gave to him, showing that he had been resurrected bodily. Then he led them out to Bethany on the Mount of Olives, where he blessed them and “was carried up into heaven” (see Luke 24:13–53).

FROM SYMBOL TO RELIC

HOW JESUS’ CUP BECAME THE GRAIL

Throughout the long history of Christianity, the Holy Grail has served primarily as a symbol. As Ben Witherington III notes in the preceding article, no early Christian writings indicate that the cup used at the Last Supper survived or was preserved as a relic. Jesus’ first followers regarded the cup as a symbol of salvation, and nothing else. In modern times, the vessel now known as the Holy Grail has become a metaphor for any ever-elusive ideal or never-ending quest.

But in the late Middle Ages—in the late 12th and 13th centuries—and again in the 19th century, the search for this relic of the Last Supper was transformed into a very real mission—one that consumed the passions, money and blood of seekers.

THE PASSION, CRUCIFIXION AND RESURRECTION

We have three subjects. The three subjects are the crucifixion, the burial and the resurrection of Jesus.

What do we know about Jesus? Nothing at all from Christian sources. We would know about Jesus from Josephus and Tacitus. They agree on three points. First, there was a movement. Second, the authorities—Tacitus mentions just the Romans, Josephus mentions the higher authorities of the Jews and the Romans—crucified Jesus to stop it. Third, it didn’t work, and the movement continued to spread.

Those are three historical facts that you should not forget. There was a movement, and authorities killed the mover, but now it has spread all over the place.

THE RESURRECTION OF RESURRECTION

Christianity was born into a world where one of its central tenets, the resurrection of the dead, was widely recognized as false—except, of course, by Judaism. Thinking about Easter is asking whatever happened at Easter? It was not resuscitation. Easter does not mean that Jesus resumed his previous life as a finite person in flesh, that is as man within human condition.

What about Easter? The question implies two other questions. The first is “What happened?” How bodily or physical was Easter? Did something happen to the corpse of Jesus? Was the tomb empty? The second question is “How are we to understand the Easter stories?” Should we regard them as reports of events that could, in principle, have been recorded with a video-camera? If not, what then are they? Are they fabrications made up to legitimate early Christianity? Or is there another way of understanding them, neither as videocam accounts nor as fabrications?

Jews believed in resurrection, Greeks believed in immortality. So I was taught many years ago. But like so many generalizations, this one isn’t even half true. There was a spectrum of beliefs about the afterlife in first-century Judaism, just as there was in the Greco-Roman world. The differences between these two sets of views and those that developed among the early Christians are startling.

Let’s begin with the Greeks. Some Greeks (and Romans) thought death the complete end; most, however, envisaged a continuing, shadowy existence in Hades. Homer, for example, tells of a murky world full of witless, gibbering shadows that must drink sacrificial blood before they can think straight, let alone talk. For Homer, Hades was no fun.1 The “soul” in Homer, though, was not the “real person,” the immortal element hidden inside a body, but rather the evanescent breath that escaped. The true self remained lifeless on the ground.

[Dr. Radhika Pandit lives in London, she had a doctorate in Psychology and Religious Studies. With five other friends she edits the writings of Prof. Dr. William R. Da Silva for publications]

| Comments on this Article | |

| Alphonse Mendonsa, Pangla/Abu Dhabi | Sat, March-30-2013, 1:28 |

| An excellent researched article. a bit lengthy but worth the read and very informative. All may not agree with certain facts but nevertheless a must read for all Christians. Thanks a lot Dr. Radhika for publishing this article of Dr. William R. D Silva. Keep contributing more in Bellevision. | |

| Eugene D Souza, Moodubelle | Fri, March-29-2013, 8:56 |

| A thoroughly researched scholarly article by Dr. William R. DSilva appropriately edited by Dr. Radhika Pandit. The article tries to bridge the faith with facts. | |

Write Comment

Write Comment E-Mail To a Friend

E-Mail To a Friend Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter  Print

Print